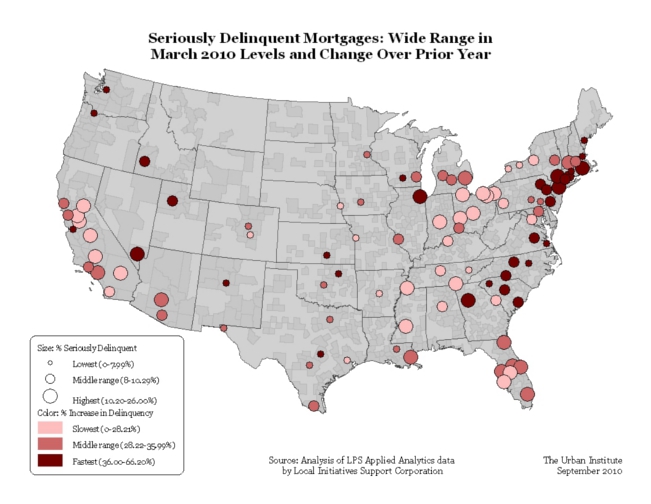

Numbers Increasing Everywhere, but Differences Between Metropolitan Areas Are Stark

In the 100 largest metropolitan areas nationwide, the average share of all home mortgages that were seriously delinquent stood at 7.7 percent in March 2009, a level that would have been considered inconceivably high just a few years ago. Yet over the subsequent year, that average climbed even higher to reach 10.2 percent in March 2010. The Mortgage Bankers Association defines "seriously delinquent" mortgages to include all those in foreclosure plus others delinquent for 90 days or more.

Focusing solely on the average rate of serious delinquencies, however, is misleading because both the severity and the trajectory of the problem vary so dramatically across metropolitan areas. Austin, TX had the lowest share seriously delinquent in March 2010 (4.4 percent) while, at the other extreme, Miami?s level was six times that high (a truly unprecedented 26.0 percent). And over the preceding year, Austin?s share increased by just 1.3 percentage points while Miami's shot up by 6.6 points.

view pdf

When the foreclosure crisis began, metros in California were hardest hit, with Florida, Arizona, and Nevada close behind. Now, however, five of the six metros with the highest delinquency rates are in Florida (Miami, Orlando, Lakeland, Tampa and Bradenton). These five metros had an average of 21.2 percent seriously delinquent in March 2010, up by 5.0 points over the previous year. The top five California metros (Riverside, Stockton, Modesto, Bakersfield, and Fresno) are also suffering (with an average delinquency rate of 16.6 percent) but their rate of increase has slowed considerably, up only 2.3 points over the year.

Interestingly, eight of the ten metros with the lowest rates of serious delinquency were in the nation?s mid-section: Austin, Madison, Omaha, Des Moines, San Antonio, Colorado Springs, Wichita and Tulsa ? the other two being Raleigh and Lancaster. Rates for these ten ranged from 4.4 to 6.5 percent and annual increases were also much smaller, ranging from 1.0 to 1.9 points. Still, it is worth remembering that even these levels are seriously problematic when considered in relation to decades of much lower rates prior to start of the mortgage crisis in 2007.

Table 1 arrays the 100 metros by the share of their mortgages that were seriously delinquent in March 2010, against the percent increase in that share over the preceding year, dividing the metros in thirds along each dimension. For those in the top band, seriously delinquent mortgages accounted for 7.9 percent or less, but for 10.3 percent or more for those in the bottom band. Those in the left hand column had experienced increases in seriously delinquent shares of 28 percent or less, while those in the right hand column had experienced increases of 38 percent or more.

view pdf

The measures are not strongly correlated. There are many metros in the upper right hand box (low delinquency rates but large increases in those rates) and in the lower left hand box (the reverse).

Clearly, all those in the bottom band (highest shares seriously delinquent, range from 10.3 percent to 26.0 percent) are places to worry about. However, it may be that the places of greatest concern at this point are those where the problem is getting worse fastest; the right hand column, with huge increases in the seriously delinquent share over the past year. This includes those in the lower right hand corner (New York, Providence, et al - worst on both counts), but it should also include those with rapid increases in the middle range of share values as well. This group includes places like Bridgeport, Salt Lake City, and Charleston, where shares seriously delinquent were in the 8.5-8.8 percent range but those shares had increased by more than an astounding 60 percent in the past year.

What explains these groupings? It is not location - with a few exceptions, metros in same regions do not cluster together. Multivariate analysis would be needed to answer this question well, but the data on Table 2 provides some clues.

First, it is clear that the economies of those in the bottom band (highest share seriously delinquent) have been much harder hit than those in the two bands above it: recent annual employment decline averaging 2.0 percent vs. 1.3 percent for the middle group, unemployment rate of 11.5 percent vs. 9.2 percent for the middle group. Similarly, as would be expected, those with the largest delinquency problems have suffered the largest declines in housing prices over the past year: average drop of 12.5 percent vs. 9.4 in the middle group. Those in the bottom band also experienced notably higher densities of subprime lending in the peak 2004-2006 period: 49.1 high cost loans originated per 1,000 existing units, compared to 31.6 for the middle group.

view pdf

None of the above measures, however, seem to define what it is that influences the rate of increase in delinquency shares; i.e., values for these measures in the right hand column (most rapid increases) are not typically much different from those for the middle and left hand columns. But one measure does make a difference, and in the expected direction. Increases in mortgage delinquency have been most rapid in metros with the biggest relative gap between home prices and local incomes. The ratio of average home price to average homeowner income in the metros in the right hand column is well above the comparable ratios for the others, particularly in the groups where delinquency rates are lower (4.2 vs. 2.9 in both cases). Further analysis of the drivers of changes in these markets should be a priority.

Metropolitan level data on the number of new mortgages becoming delinquent or moving into foreclosure have been available before, but this is the first information made public for metropolitan areas on the total share of all mortgages that are seriously delinquent (arguably a better indicator of housing market stress since it looks at the full extent of the problem rather than just the number entering the pipeline). A mortgage is considered to be ?in foreclosure? if a notice of intent to foreclose has been sent to the borrower but the case has not been cleared, either through remediation or a final foreclosure sale.

The information comes from calculations by the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) based on nation-wide data provided by LPS Analytics and the Mortgage Bankers Association. A description of the calculation methodology, as well as tables from this source showing the data on mortgage delinquency and foreclosure for the 100 metros individually can be found at Foreclosure-Response.org.