What Will it Take to Put Affordable Housing Within Reach?

Why don't they just get a job? Whether it is asked rhetorically or in earnest, whether it is explicit or implicit, this question remains central to the debate about housing and homelessness and welfare policy in general in the United States.

Each year the National Low Income Housing Coalition publishes Out of Reach, a report that addresses this question by simply asking, what if a family or individual has one or more full time jobs at prevailing wage levels? Is this sufficient to assure them a decent affordable home?

The Housing Wage, the report?s central statistic, represents the hourly wage a household would have to earn, working 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, in order to pay the HUD Fair Market Rent (FMR) for an appropriately sized rental home without paying more than 30% of income. The FMR is the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development?s estimate of what a household needs to be able to pay in rent and utilities for a modest rental house or apartment. In most areas, the FMR is the 40th percentile rent in the local rent distribution, adjusted for substandard and luxury units.

In 2010, the national average two-bedroom Housing Wage is $18.44, more than twice the federal minimum wage of $7.25. And despite recent increases to the minimum wage, the gap between the minimum wage and the Housing Wage has steadily widened over the last decade.

view larger image

Nationally, in the past ten years, nominal wage levels in the United States have risen 38% and the federal minimum wage has increased 40%. But in this same period the price of a modest rental home, measured by the two-bedroom FMR, has increased 45%. The current recession has only exacerbated this as wages and incomes have fallen faster than rents in most markets across the country. Nationally, the wage to afford the FMR for even a one bedroom rental ($17.11) exceeds the national median wage ($15.95 in May 2009).

The top 100 metro areas have seen roughly the same average rate of growth in the cost of rental housing as the rest of the country. However, when we break this down into the MetroTrends categories based on how metropolitan areas are faring in the current economy, we see considerable variation among metro areas. The ?double trouble? metros, those with declining jobs and for-sale home values, saw the fastest growth in the cost of modest rental housing this decade, as measured by the two-bedroom FMR. Interestingly, the group of metros where for-sale home prices have fallen but employment has held steady have also seen fast growth in the housing wage since 2000.

view larger image

In the midst of the housing bubble, areas with hot housing markets generally had low unemployment, often directly tied to the strength of the construction and real estate sector. The strong labor market also fueled the demand for rental housing - particularly by lower wage, younger, and immigrant households - and rents increased rapidly. In many areas, the speculative conversion of rental housing to the for-sale market shrunk rental supply and further contributed to the rise in rents. When the bubble burst, the areas with above-average rent growth for most of the decade had generally also experienced outsized growth in home prices and subsequently saw dramatic home price reversals.

Thus far, however, rents have not declined in step with home prices because the demand for rental housing has increased dramatically. According to the most recent numbers from the Census Bureau?s Housing Vacancy Survey, for example, the number of renter households nationwide is estimated to have increased by nearly a million from the second quarter of 2008 to the second quarter of 2010, because as the nation lost 615,000 owners it gained 1.6 million new renters.

The Housing Wage itself remains higher on average in these bubble affected areas. The ?double trouble? areas saw the fastest growth and have the second highest Housing Wage, putting low income households in these areas under particular stress.

view larger image

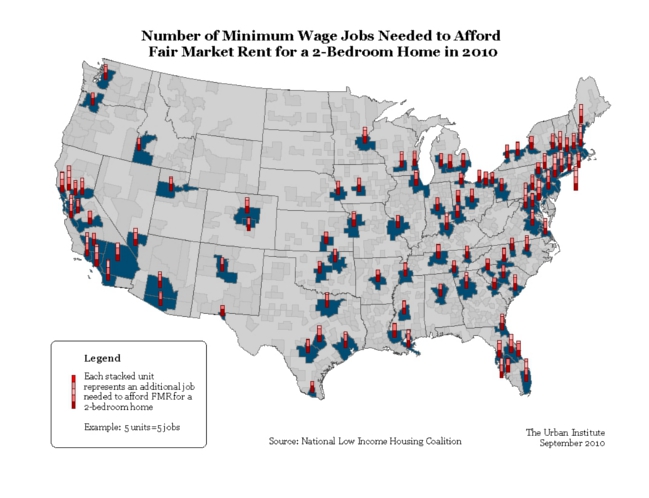

Though the costs of modest rental housing may be lower in some metropolitan areas, we find that in every one of the top 100 metro areas, including low cost areas like Wichita, KS; Youngstown, OH; El Paso, TX; and Scranton-Wilkes-Barre, PA, it takes at least 1.3 jobs paying the state?s minimum wage to afford the FMR for even a one-bedroom apartment. In fact, there is not a metropolitan area or rural county in the country today where a household earning the equivalent of a full time job at the minimum wage can afford a one bedroom apartment at the local FMR.

view larger image

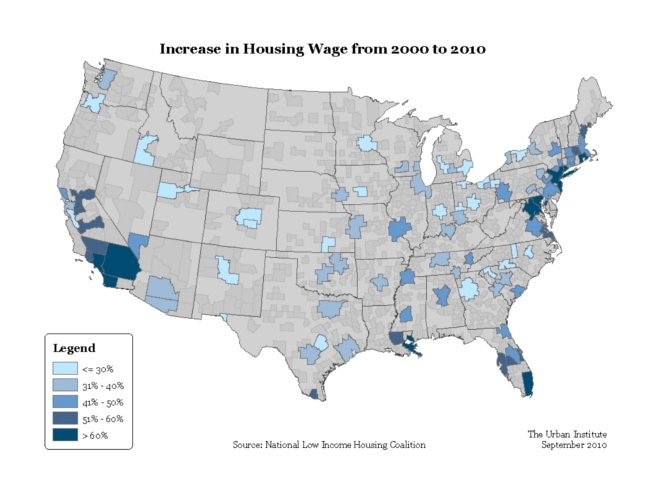

Looking nationwide shows that while the metropolitan areas in the Northeast and West have the highest Housing Wages, those in the West and the South have seen the fastest growth in what a household needs to earn to be assured an affordable home.

view larger image

What these Housing Wage comparisons tell us is that ?just getting a job, any job? is not sufficient to assure someone a decent, affordable home. In most metropolitan areas, earning an income equivalent to two or even three times the minimum wage is insufficient. The full Out of Reach report compares the Housing Wage to a variety of benchmark wage and income levels, making clear why many Americans, not just those with the lowest incomes, have difficulty paying for their housing and making ends meet.