Our metropolitan spotlights focus on selected metros, showing how they're faring relative to others in their region and nationally.

New York Metropolitan Area:

New York's Multi-Family Housing Stock: A Different Story

The New York metro area has survived the recession better than many other areas of the country. While October 2010's 8.5 percent unemployment rate was alarming by historical standards, it compared to 9.4 percent in the top 100 metro areas. Although housing prices fell during the recession, they did not fall as far as in other places; prices for single-family homes in the metropolitan area fell by 19 percent between 2006 and the end of 2010, compared to 22 percent in other large metro areas. We must make a distinction, however, between New York City itself and the metropolitan area as a whole. While housing prices for single-family homes in New York City fell by 32 percent between 2006 and 2010, this building type accounts for only about 15 percent of all residential units in the city. Most households in the City of New York are renters (66 %), compared to 47 percent in the metro area and 34 percent in the country as a whole. Renters in New York City are also far more likely to live in large buildings, which are subject to a different set of challenges.

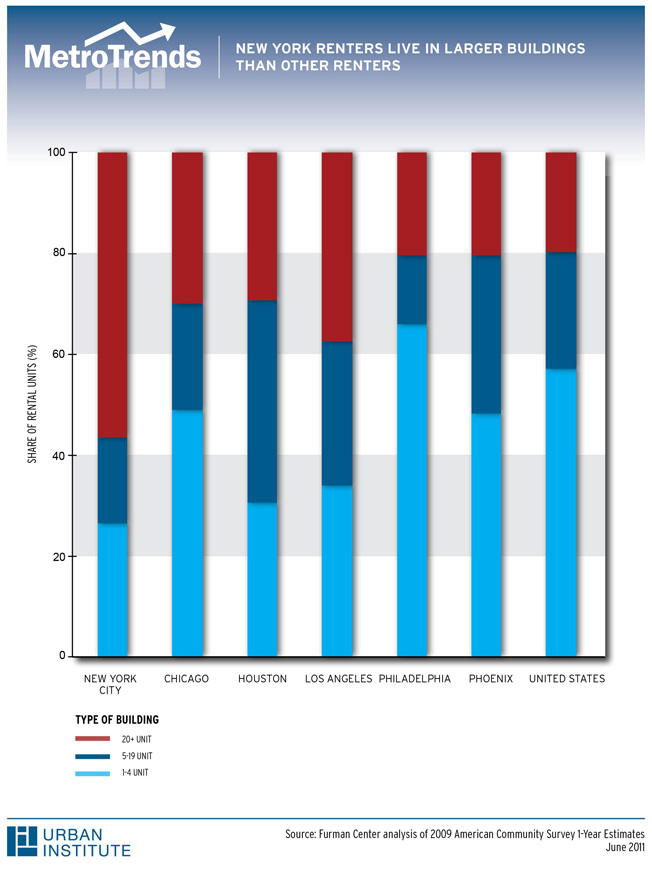

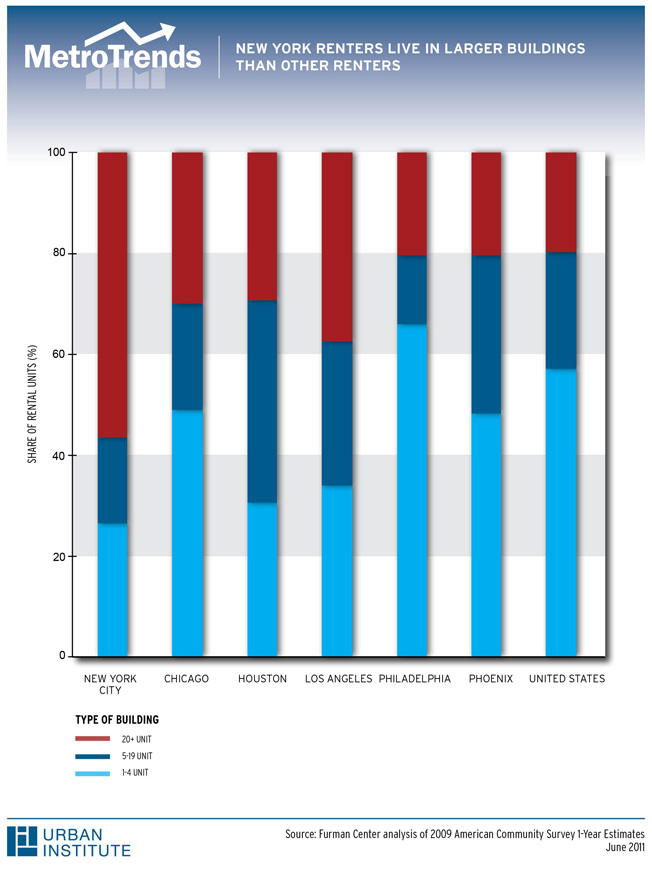

As reported in our State of New York City’s Housing and Neighborhoods: 2010 report, multi-family rental properties (defined as properties with five or more units) house more than four in ten New Yorkers, allowing for an average density of almost 28,000 people per square mile, a level that dwarfs that of other large U.S. cities. The next most densely populated city is Chicago, with less than 13,000 per square mile. New York doesn't just have more multi-family buildings than other cities; rental buildings in New York City are considerably larger. Fifty-seven percent of all rental units in New York City are in buildings with 20 or more units, compared to only 20 percent of all rental buildings in the United States. Even in Chicago, only 30 percent of all rental units are in these large buildings.

The multi-family housing stock in New York City is at least as vulnerable to the housing crisis as the single-family stock. Multi-family properties are often financed through ballooning commercial mortgages, which require the owner to pay only a small monthly payment for a term of five or ten years until the mortgage "balloons." At this point, the borrower is required to pay back the entire outstanding amount. Typically, property owners refinance when the mortgage comes due, which may be a struggle if the property value has depreciated considerably. Further, an owner's ongoing ability to cover mortgage payments relies on sounds estimations of rent rolls, which are likely to be more volatile in a recession.

In New York City, most landlords are prohibited from rapidly increasing rents in response to rising operational or financing costs. In addition to strong tenant protection laws, nearly three of every four units in a New York City multi-family rental building are rent-regulated, or subject to strict rental increase limitations from the Rent Guidelines Board. Designed to maintain stability for tenants, rent regulation typically means that tenants who have lived in properties for a considerable period of time will pay much less than new tenants; in 2008, tenants who had lived in a multi-family unit for less than three years paid a third more than tenants who moved into their units in the 1990s.

Owners sometimes borrow under the assumption that they can increase turnover of existing residents and charge market-rate rents once rent levels reach the threshold levels. This strategy is not always successful, as evidenced by the much-publicized $5.4 billion acquisition, and subsequent foreclosure, of Stuyvesant Town. When rent-regulation is the result of specific tax abatement or preservation programs, potential buyers may not even be aware of the full extent of their rent limitations since these programs are often managed by a variety of city and state agencies, and the restrictions are sometimes only noted in paper filings. In other cases, owners may be fully aware of rent regulations but merely overestimate their chances of getting the restrictions removed.

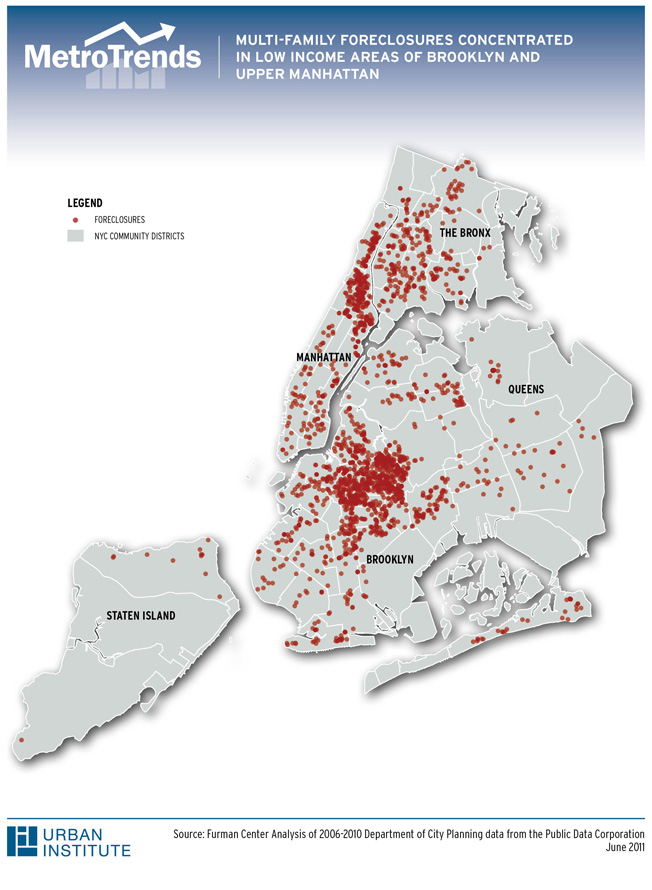

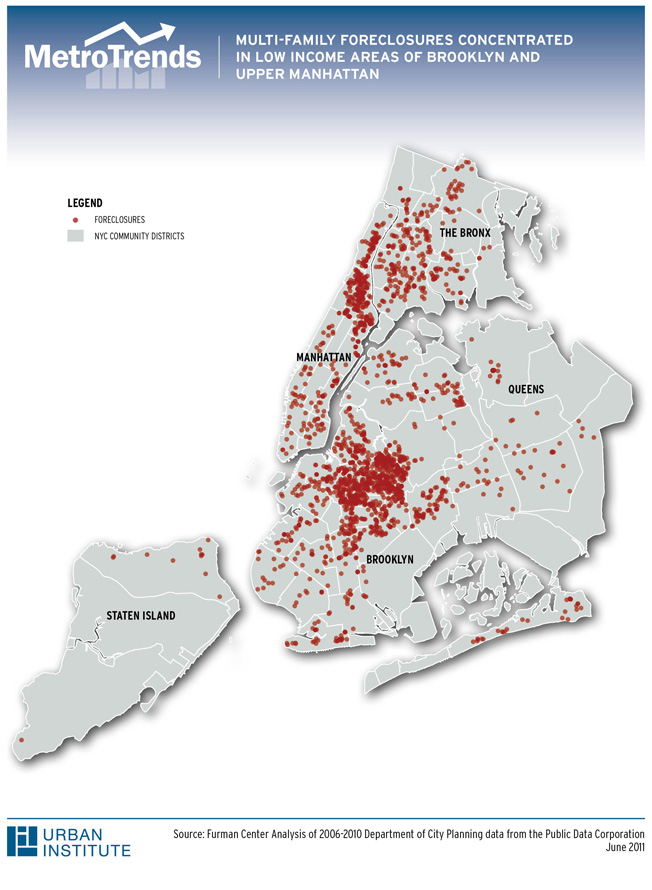

Between 2006 and the end of 2010, more than 2,000 different multi-family rental properties received a notice of foreclosure. This has disproportionately affected New York City's low-income and minority residents for two reasons. First of all, residents of multi-family rental buildings are more likely to be low income or Hispanic. The median household in a New York City building with five or more units has an income of only $36,200 compared to a $51,000 median income for the city as a whole, and fifty percent of New York City's Hispanic households live in multi-family buildings compared to only 36 percent of non-Hispanic white households.

Second, foreclosures on multi-family properties have been concentrated in low-income neighborhoods with high shares of minorities. For example, Bedford Stuyvesant, a Brooklyn neighborhood where 82 percent of residents are black or Hispanic and the median income is $39,000, is home to more than 11 percent of all multi-family properties that have received a foreclosure notice since 2006.

The multi-family mortgages that were financed in 2006 and 2007 have yet to be refinanced and will be ballooning soon. The loss of value from the decline in housing prices may result in borrowers who are underwater and are unable to cover the balloon payments. This could spark another round of foreclosures in upcoming years. Furthermore, rent rolls have not kept pace with operational costs over the last decades. This is an issue that would have been important even in the absence of an economic slump but has special significance in the current market. As New York City begins to recover from the recession, the next few years pose significant challenges, the outcomes of which are critical to New York City's ability to house a diverse population.

The Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy is a joint center of the New York University School of Law and the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service at NYU. Since its founding in 1995, the Furman Center has become the leading academic research center in New York City devoted to the public policy aspects of land use, real estate, and housing development. The Furman Center is dedicated to providing objective academic and empirical research on the legal and public policy issues involving land use, real estate, housing and urban affairs in the United States, with a particular focus on New York City. Click here for more information on the Furman Center.